Consonant Alignment

As choir directors, we talk a lot about "vowel alignment," but today I want to discuss alignment of a different kind: that on the printed page.

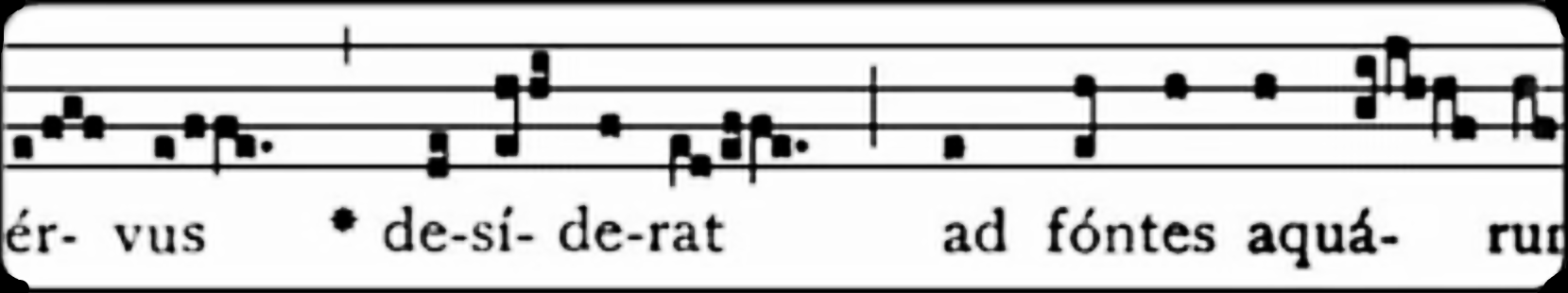

One of the interesting things that I learned from Dr. James Jordan during his clinic earlier this week (which was such a small detail that I had never even noticed it) is that, in original chant notation, the notation of the neumes (notes) line up with the vowel of the Latin text, not the consonant. In this way, it helps the singer visually identify that the vowel is what carries the sound, and that the consonants should be "dropped in," not over-emphasized. This is good vocal technique, and we all know it, but I never realized how helpful that could be until we began singing chant together. Small though it may be, it makes a difference! Take a look at the example below.

Now, this got me thinking about something about something I've been pretty adamant about in my own notation for some time now, which is where to place the consonants in multi-syllable words. For example, in Tonic of Wildness, mm. 13-15:

Notice how the word "under" is notated, with the "n" on the second syllable, rather than the first. In traditional notation, you would see it like this:

... which may be easier to read, but to my mind, when I see "un-der," it makes me (as a singer) subconsciously want to close to the "n" consonant. In fact, when I have explained how we "sing on the vowel" to my own students, I have had multiple ask me: "Then why is it written like that?" To which I am forced to reply: "That's just the way it's done."

Well, not in my house. To make my music easier to sing on the vowel, I consistently notate my lyrics ending on a vowel when at all possible.

Now, this can sometimes get a little hairy, admittedly, like in this case from Where the Sidewalk Ends, (now "The Moment") mm. 21-22, where the word "asphalt" looks like a nasty consonant-cluster. But would you really like your kids to go to the "s" early on the word "asphalt?" Think about it.

Sometimes I even take it further, like in Prayers of Steel, mm. 2-4:

You can see that the word "anvil" has been re-aligned, as has already been explained: but I've also extended the word "God" to not even include the "d" until the cutoff. In this case, it's because I explicitly want a strong shadow vowel on the cutoff. But is it appropriate in other places?

For example, today I'm working on a setting of Maya Angelou's "Caged Bird," and there is a passage like this:

Following my own logic, it should say "free-do-----(m)."

In all honesty, I would prefer to notate it that way. But just like the "transposition/concert pitch" issue, or the fact that (by and large) we still notate rhythms using confusing time signatures like 3/8 and 6/8 instead of the far more logical system provided by Carl Orff (see right), I'm afraid that some notational headaches may be here to stay. If we begin to "give in" to all the pressures to re-notate things so that they are "easier to read" we may have a huge mess on our hands, and then no one will perform our music.

Still, if anybody wants to start a revolution... you know where to find me.